Twitter is not what it seems. The social-media platform poses as a neutral marketplace for the exchange of ideas and information; an agora where journalists, politicians, academics, cultural icons, business titans, and ordinary citizens can engage in a dialogue unbounded by gatekeeping elites.

But it is actually a tool of progressive power. While you were hypnotized by viral memes, a cabal of social-justice STEM majors seized the commanding heights of the attention economy. And they have been using it to bend the mass public to their will. By subtly manipulating which forms of speech do and do not gain prominence — and/or simply banishing wrongthink from its platform — Twitter imposes woke orthodoxy on the nation’s youth while insulating the liberal elite from popular rebuke. This information warfare hasn’t merely cost conservative commentators followers or retweets; it cost a Republican president the White House.

That’s the story that conservatives want to tell about what Twitter used to be, in the bad old days before Elon Musk begrudgingly bought it. Fortunately, Twitter’s new CEO has a deep-seated objection to social-media companies using their power over discourse to promote partisan causes. Therefore, Musk is using his newfound power over discourse to promote the conservative movement’s demagogic narratives about Twitter and the Democratic president’s son.

Specifically, Musk delivered a vast trove of internal Twitter documents to two independent journalists, Matt Taibbi and Bari Weiss, who have long endorsed aspects of the GOP’s indictment of the platform. Taibbi and Weiss proceeded to publish a pair of exposés on Twitter’s inner workings. Dubbed “the Twitter Files,” these reports featured a couple genuinely concerning findings about pre-Musk Twitter’s operations. But they were also saturated in hyperbole, marred by omissions of context, and discredited by instances of outright mendacity. Musk’s commentary on the Twitter Files, meanwhile, proved even more demagogic and deceptive than the exposés themselves.

For these reasons, the Twitter Files are best understood as an egregious example of the very phenomenon it purports to condemn — that of social-media managers leveraging their platforms for partisan ends.

Everything you probably don’t need to know about Hunter Biden’s laptop.

The first installment of the Twitter Files concerned the social-media platform’s suppression of an October 2020 New York Post article about emails ostensibly recovered from Hunter Biden’s laptop. To appreciate how unhinged the conservative narrative about the “Twitter Files” is, and how irresponsible Musk’s presentation of them has been, one must first understand the flimsiness of the article that kicked off the whole controversy.

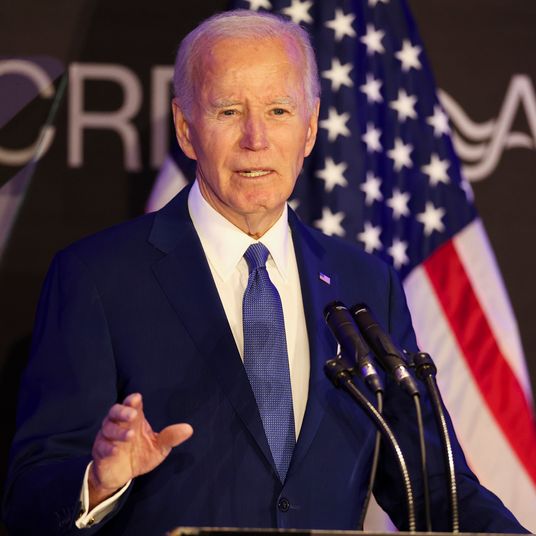

In the Post’s telling, the emails on Hunter Biden’s laptop contained dispositive evidence that Joe Biden had used his power as vice-president in 2015 to advance the interests of Burisma, a Ukrainian natural-gas company that had employed Hunter Biden. In the conservative media’s account, meanwhile, Hunter’s “laptop from hell” proved that Joe Biden had engaged in acts of corruption so wanton that they made Donald Trump look like Ralph Nader.

In reality, neither the Post’s reporting nor any subsequent investigations of Hunter Biden’s laptop (or his relationship with Burisma) has documented a single instance in which Joe Biden used public power to aid his son’s private interests.

There is little question that Hunter Biden was an influence peddler who sought to monetize his access to the American vice-president. Burisma was not paying Hunter $50,000 a month for his expertise on the Eastern European natural-gas market. It was paying to be one degree of separation away from Hunter’s father.

This is sordid. But it’s also mundane. If influence peddling were illegal, K Street would house a sprawling penitentiary. Hunter monetizing his last name is not a noteworthy scandal. Joe Biden changing U.S. policy to aid that monetization effort would be. Thus, the key claim in the right’s narrative about the “laptop from hell” is that Joe Biden pressured the Ukrainian government to oust its prosecutor general so as to protect Burisma from legal scrutiny.

The Post purported to substantiate that claim, but in reality did no such thing. The tabloid did uncover an apparent email that Vadym Pozharskyi, an adviser to the board of Burisma, had sent to Hunter Biden in April 2015, wherein Pozharskyi thanked Hunter for “inviting me to D.C. and giving an opportunity to meet your father and spent [sic] some time together.” Given unfettered access to 217 gigabytes of (what was ostensibly) Hunter Biden’s personal data, this was the closest the Post could come to evidence of Joe Biden’s corruption: an email that suggested that one of Hunter’s associates at Burisma had some unspecified form of contact with Joe Biden during a trip to D.C. The message does not indicate that Pozharskyi received a private audience with the vice-president, let alone one in which he got to lobby Biden for Burisma’s interests.

Nevertheless, the Post characterized this as a “smoking-gun email.” It proceeded to assert that after his meeting with Pozharskyi, the “elder Biden pressured government officials in Ukraine into firing a prosecutor who was investigating the company.” This was false.

It is true that, as vice-president, Joe Biden pressured Ukrainian president Petro Poroshenko to fire Prosecutor General Viktor Shokin. But Biden did so at the behest of a coalition of Western interests. In addition to the U.S. government, the International Monetary Fund, World Bank, and European Union all believed that Shokin was complicit in endemic corruption that was diverting development funds to oligarchs. And not without reason. Troves of diamonds, cash, and other assorted valuables were discovered at the homes of Shokin’s underlings, indicating that they had been taking bribes. Yet the Ukrainian prosecutor’s office declined to take the officials to court; individual prosecutors who tried to pursue the case were fired or resigned.

In truth, Shokin was not fired for investigating Burisma but for the opposite; one of the West’s complaints about his office was that it failed to pursue a corruption inquiry against Burisma founder Mykola Zlochevsky.

The Post claimed otherwise solely on the basis of statements that Shokin made after losing his job. Beyond the fact that Shokin is an unreliable narrator with a clear motive to disparage Joe Biden, even Shokin’s remarks themselves did not actually support the tabloid’s claims: While the Post reported that Shokin “was investigating” Burisma at the time he was fired, Shokin only claims that he had made “specific plans” to investigate the company. Conveniently, whereas an active investigation could be affirmed or falsified by a paper trail, it is impossible to disprove what Shokin did or did not “plan” to do.

All of which is to say: On its face, the New York Post story was dishonest and misleading.

And at the time of its publication, it was far from clear that the story could be taken at face value. On its way from Hunter Biden’s custody to the New York Post’s, Biden’s data passed through several different hands, including those of President Trump’s attorney Rudy Giuliani, who had been on a crusade to generate incriminating information about the Bidens’ relationship with Burisma. Anyone in that chain of custody could have added files to the laptop. The primary author of the Post’s story refused to put his name on it out of concern that the tabloid had failed to confirm the veracity of the documents in question.

Subsequently, forensic analysts would confirm the authenticity of some of Hunter Biden’s documents, while concluding that much of the data lacked the cryptographic signatures necessary for verification.

The Constitution does not give you an inalienable right to retweet Hunter Biden’s genitals.

In the summer of 2020, federal law enforcement had told Twitter executives to be on guard against possible foreign hacks aimed at influencing the U.S. presidential election. These concerns were, of course, informed by the fact that Russian agents had hacked Democratic Party emails in 2016 as part of a political interference campaign.

In this context, the Post’s Hunter Biden story raised red flags with Twitter’s content-moderation team. After all, that story consisted of ill-gotten emails fed to the Post by Donald Trump’s lawyer, who’d spent months consorting with Trump sympathizers in Eastern Europe. The platform responded by taking the extraordinary step of suppressing the story on its platform, marking it as unsafe and even preventing Twitter users from sharing it via direct message.

In “The Twitter Files, Part One: How and Why Twitter Blocked the Hunter Biden Laptop Story,” Matt Taibbi sheds light on Twitter’s internal deliberations over this decision. Taibbi frames his findings as a demonstration of Twitter’s bias in favor of Democrats. But his reporting does little to support that claim.

In company email exchanges obtained by Taibbi, Twitter safety chief Yoel Roth and Deputy General Counsel Jim Baker explained that they had chosen to mark tweets linking to the Post story as “unsafe” on the grounds that such tweets disseminated “hacked materials,” a violation of Twitter’s terms of service. Both Roth and Baker acknowledged that they did not actually know that the Post’s piece was based on hacked materials. “Given the SEVERE risks here and lessons of 2016,” however, Roth explained, “we’re erring on the side of including a warning and preventing the content from being amplified.”

In the version of pre-Musk Twitter conjured by conservative rhetoric, one would expect universal assent to this judgment, if not, replies reading, “Yes! This is an excellent pretext for a coup against the bad orange man!” But Taibbi’s documents actually reveal internal skepticism of the decision, and expressions of ambivalence even from those who endorsed it. Taibbi quotes an anonymous former employee as saying, “Hacking was the excuse, but within a few hours, pretty much everyone realized that wasn’t going to hold. But no one had the guts to reverse it.” This makes it sound as though Roth’s avowed concerns about hacking were just a fig leaf for suppressing a story inconvenient for Democrats.

Yet despite having access to virtually all of Twitter’s internal communications, Taibbi produced no actual evidence that the decision was motivated by anything beyond concern that Twitter would find itself complicit in promulgating hacked materials.

The closest thing Taibbi has to evidence of untoward partisan influence is an email from the Biden campaign flagging several Hunter-related tweets for Twitter’s content moderators, who then “handled” them. But all of these tweets appeared to feature nude photos of Hunter Biden that were non-consensually shared, an unambiguous violation of Twitter’s terms of service. Taibbi, for his part, chose not to provide his readers with that context. The reporter did however acknowledge that there was nothing unusual about the Biden team’s outreach, and that the Trump White House also routinely sent Twitter content moderation complaints.

Regardless, Twitter recognized that it had overreached and ceased blocking links to the New York Post story after only one day. By suppressing it for such a short period of time, while generating a giant media controversy about the story, it is plausible that Twitter’s decision-making actually increased the Post article’s reach.

In sum: The New York Post published a story based on data that was apparently — but, at the time, unverifiably — Hunter Biden’s. That story falsely purported to offer “smoking gun” evidence of Joe Biden’s corruption, when it actually provided no such thing. Faced with warnings from federal law enforcement about impending foreign hacks, and a story based on apparently stolen emails sourced from Rudy Giuliani, Twitter’s content moderation team chose to suppress the Post article. That decision was internally controversial, and even those who supported it said that they wished they had more information about the source of the emails. Within 24 hours, Twitter reversed course. It is possible that this reduced the ultimate reach of the Post’s story, which, given that story’s mendacious content, probably would have been beneficial to public understanding of the Trump-Biden race (after all, there was exponentially more evidence that Donald Trump had used public power to advance his family’s private business interests than evidence that Biden had done so, yet the Post’s story conveyed the opposite impression). But it’s also possible that Twitter’s decision actually increased the story’s prominence by endowing it with an aura of forbidden knowledge. Separately, when the Biden campaign flagged tweets that featured pornographic images, Twitter responded by enforcing its own rules.

Or, as the likely next Republican House Speaker Kevin McCarthy put it after the Twitter Files were released, “We’re learning in real-time how Twitter colluded to silence the truth about Hunter Biden’s laptop just days before the 2020 presidential election.” House Republican James Comer declared Twitter’s actions tantamount to “election suppression.” Former Republican Senate candidate Blake Masters, meanwhile, declared, “Any candidate who explained how Big Tech put its thumb on the scale was called an ‘election denier’ — but the simple truth is that the Hunter Biden laptop censorship put Biden into the White House, full stop.” Donald Trump went so far as to announce that the Twitter Files had invalidated the 2020 election, arguing that “A Massive Fraud of this type and magnitude allows for the termination of all rules, regulations, and articles, even those found in the Constitution.”

If Elon Musk was alarmed by the way his ostensibly apolitical gesture of transparency was aiding a partisan messaging campaign, he gave few indications of such disquiet. To the contrary, Musk joined red America’s hyperventilating mob in telling histrionic lies about what the Twitter Files actually showed.

“If this isn’t a violation of the Constitution’s First Amendment, what is?” Musk tweeted, going on to explain, “Twitter acting by itself to suppress free speech is not a 1st amendment violation, but acting under orders from the government to suppress free speech, with no judicial review, is.”

Of course, nothing in Taibbi’s reporting indicated that Twitter had suppressed the Post story at the request of the Biden campaign, let alone of government officials. And even if it had, so long as the government did not coerce Twitter into suppressing the Post story, there would still have been no constitutional violation; the government is allowed to ask private actors to keep information secret. Indeed, U.S. officials routinely ask national security reporters not to publish certain facts whose exposure would, in their view, compromise U.S. interests.

One week later, Musk has yet to delete or retract his tweets, despite the fact that they unambiguously misrepresent Taibbi’s reporting. Instead, the Twitter CEO has carried on affirming the conservative movement’s false claim that the Post story’s suppression represents a constitutional crisis.

What Bari Weiss doesn’t want you to know about Twitter’s political biases.

The second installment of the Twitter Files had a bit more substance than the first. But like its predecessor, it affirmed conservative narratives of persecution by omitting key pieces of context, while also including one outright lie.

Bari Weiss’s exposé sought to illuminate Twitter’s policy of secretly reducing the reach of certain accounts and tweets. Twitter has a range of tools for disciplining users that violate its terms of service. Most of these are apparent to users: If your account is suspended or banned, you typically receive a message from Twitter indicating the offensive tweets and giving you an opportunity to appeal their decision.

But this is an imperfect tool in some instances. For example, if a Twitter account is engaging in spam or scammy behavior, blocking their account might just lead them to create another and continue offending. By contrast, if the platform simply reduces the visibility of that account’s tweets, the account will be more likely to carry on spamming only now without degrading Twitter’s user experience.

Twitter has made no secret of the fact that it punishes accounts by limiting their visibility. Since at least 2018, Twitter’s help page has said, “When abuse or manipulation of our service is reported or detected, we may take action to limit the reach of a person’s tweets.” Twitter also listed “Limiting tweet visibility” as an enforcement option under the company’s terms of service, writing, “This makes content less visible on Twitter, either by making tweets ineligible for amplification in top search results and on timelines for users who don’t follow the tweet author, by down-ranking tweets in replies (except when the user follows the tweet author), and/or excluding tweets and/or accounts in email or in-product recommendations.”

Twitter’s current ownership has openly embraced this form of content moderation. Last month, Musk tweeted: “New Twitter policy is freedom of speech, but not freedom of reach. Negative/hate tweets will be max deboosted & demonetized, so no ads or other revenue to Twitter.”

Nevertheless, after reporting that the conservative commentator Charlie Kirk had been put on a “Do not amplify” list, Weiss bizarrely claimed that Twitter had long “denied that it does such things.”

Weiss did not try to reconcile that claim with Twitter’s long-standing terms of service; in fact, she did not even inform her readers of the existence of those terms. Rather, in justifying her assertion, Weiss wrote, “In 2018, Twitter’s Vijaya Gadde (then Head of Legal Policy and Trust) and Kayvon Beykpour (Head of Product) said: ‘We do not shadow ban,’” a term that she proceeds to define as “visibility filtering.”

But Gadde and Beykpour never denied that Twitter limited the visibility of some accounts. Rather, in their blog post, they wrote, “The best definition [of shadow ban] we found is this: deliberately making someone’s content undiscoverable to everyone except the person who posted it, unbeknownst to the original poster.” And Twitter does not in fact “shadow ban” in that sense of the term.

Weiss ostensibly read Gadde and Beykpour’s blog post. So, she knew that they did not actually deny that Twitter limited the visibility of some accounts. Yet she led her readers to believe that she’d caught Twitter in a lie. In other words, she deliberately misled her audience.

Which is a big problem, since we need to be able to trust Weiss in order to evaluate the legitimate concerns that her report raises. Specifically, Weiss presents evidence that Twitter may have limited the visibility of some accounts on the basis of their political views, rather than clear violations of the platform’s policies. She notes that “Stanford’s Dr. Jay Bhattacharya (@DrJBhattacharya) who argued that COVID lockdowns would harm children” was placed on “a ‘Trends Blacklist,’ which prevented his tweets from trending.” Here, Weiss implies that Bhattacharya was placed on this list because he criticized COVID lockdowns. But she doesn’t actually assert that, or provide any direct evidence for it.

Similarly, she suggests that the conservative personalities Dan Bongino and Charlie Kirk were placed on blacklists because of their political views. Yet both those commentators are provocateurs who quite plausibly might have violated the platform’s rules regarding abuse at one point or another. Weiss provides no information about why Twitter blacklisted either account. (It’s worth noting that whatever Twitter did to these accounts’ visibility, it was not very draconian, as both remain incredibly popular, and boast millions of followers.)

Weiss suggests that these blacklists disproportionately harmed conservatives. But she doesn’t actually provide any information about the ideological breakdown of blacklisted accounts. She merely observes that some of the blacklisted accounts were conservative, then suggests that this proves that they were blacklisted for being conservative.

Weiss does provide one piece of evidence for political bias in Twitter’s content moderation practices. She notes that the account “Libs of TikTok,” operated by conservative Chaya Raichik, was repeatedly suspended for publishing posts that encouraged harassment of “hospitals and medical providers” by insinuating “that gender-affirming healthcare is equivalent to child abuse or grooming.” Nevertheless, when someone tweeted Raichik’s home address, Twitter declined to take any action against a message that was seemingly intended to encourage harassment of Raichik.

On its face, this would seem to represent an inconsistent application of Twitter’s policy against tweets that promote harassment, although Weiss (reasonably) does not provide a link to the tweet in question. Her reporting nevertheless cannot tell us whether Twitter’s content moderation decisions were characterized by routine or systematic asymmetries of enforcement.

In any event, Weiss’s report lent credence to conservatives’ claim that their political movement has been systematically suppressed by Twitter’s “woke” leadership — a conviction that is demonstrably wrong.

In 2021, Twitter conducted a study of its algorithm’s political implications. Examining data from seven different countries — the United Kingdom, United States, Canada, France, Germany, Spain, and Japan — Twitter compared how tweets were presented by a default, chronological timeline versus how they appeared when curated by their company’s algorithm. It found that in six of seven nations, including the United States, the algorithm amplified rightwing politicians and news organizations far more than leftwing ones.

One could argue that this should not qualify as a form of “bias,” since the algorithm is designed on politically neutral principles. Perhaps, rightwing content is simply more engaging. After all, the most-watched cable news network is a conservative one, while the most-listened-to political radio shows are rightwing. Whatever the reason though, it is simply the case that pre-Musk Twitter’s content curation policies made rightwing content more visible — and leftwing content, less — than a purely neutral hosting of tweets would have done.

A journalist interested in impartially reporting on the political implications of Twitter’s content moderation policies might have mentioned this reality. But then, such a journalist also probably would not publish lies about which forms of content moderation Twitter did and did not foreswear in 2018.

The Twitter Files provide limited evidence that the social-media platform’s former management sometimes enforced its terms of service in inconsistent and politically biased ways. The project offers overwhelming evidence that Twitter’s current management is using the platform to promote tendentious, partisan narratives and conservative misinformation. In that sense, Taibbi and Weiss have performed revelatory journalism.